Great Zimbabwe is a medieval city in the south-eastern hills of the modern country of Zimbabwe, near Lake Mutirikwe and the town of Masvingo. It was the capital of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe from the 13th century, having been settled in the 4th century AD. Construction on the city began in the 11th century and continued until it was abandoned in the 15th century. The edifices were erected by ancestors of the Shona people, currently located in Zimbabwe and nearby countries. The stone city spans an area of 7.22 square kilometres and could have housed up to 18,000 people at its peak, giving it a population density of approximately 2,500 inhabitants per square kilometre.

Great Zimbabwe is believed to have served as a royal palace for the local monarch. As such, it would have been used as the seat of political power. Among the edifice’s most prominent features were its walls, some of which are 11 metres (36 ft) high. They were constructed of “dry stone” (that is, without mortar). The city was eventually abandoned and fell into ruin.

The word great distinguishes the site from the many smaller ruins, now known as “zimbabwes”, spread across the Zimbabwe Highveld. There are 200 such sites in southern Africa, such as Bumbusi in Zimbabwe and Manyikeni in Mozambique, with monumental, mortarless walls.

Origin of name

Zimbabwe is the Shona name of the ruins. The name contains dzimba, the Shona term for “houses”. There are two theories for the etymology of the name. The first proposes that the word is derived from Dzimba-dze-mabwe, translated from Shona as “large houses of stone” (dzimba = plural of imba, “house”; mabwe = plural of bwe, “stone”). A second suggests that Zimbabwe is a contracted form of dzimba-hwe, which means “venerated houses” in the Zezuru dialect of Shona, as usually applied to the houses or graves of chiefs.

Construction

Construction of the stone buildings started in the 11th century and continued for over 300 years. The ruins at Great Zimbabwe are some of the oldest and largest structures located in Southern Africa, and are the second oldest after nearby Mapungubwe in South Africa. Its most formidable edifice, commonly referred to as the Great Enclosure, has walls as high as 11 m (36 ft) extending approximately 250 m (820 ft). David Beach believes that the city and its proposed state, the Kingdom of Zimbabwe, flourished from 1200 to 1500.

Its growth has been linked to the decline of Mapungubwe from around 1300, due to climatic change or the greater availability of gold in the hinterland of Great Zimbabwe.

Traditional estimates are that Great Zimbabwe had as many as 18,000 inhabitants at its peak. However, a more recent survey concluded that the population likely never exceeded 10,000. The ruins that survive are built entirely of stone; they span 730 ha (1,800 acres).

Key Features

Construction of the stone buildings started in the 11th century and continued for over 300 years. The ruins at Great Zimbabwe are some of the oldest and largest structures located in Southern Africa, and are the second oldest after nearby Mapungubwe in South Africa. Its most formidable edifice, commonly referred to as the Great Enclosure, has walls as high as 11 m (36 ft) extending approximately 250 m (820 ft). David Beach believes that the city and its proposed state, the Kingdom of Zimbabwe, flourished from 1200 to 1500.

Its growth has been linked to the decline of Mapungubwe from around 1300, due to climatic change or the greater availability of gold in the hinterland of Great Zimbabwe.

Traditional estimates are that Great Zimbabwe had as many as 18,000 inhabitants at its peak. However, a more recent survey concluded that the population likely never exceeded 10,000. The ruins that survive are built entirely of stone; they span 730 ha (1,800 acres).

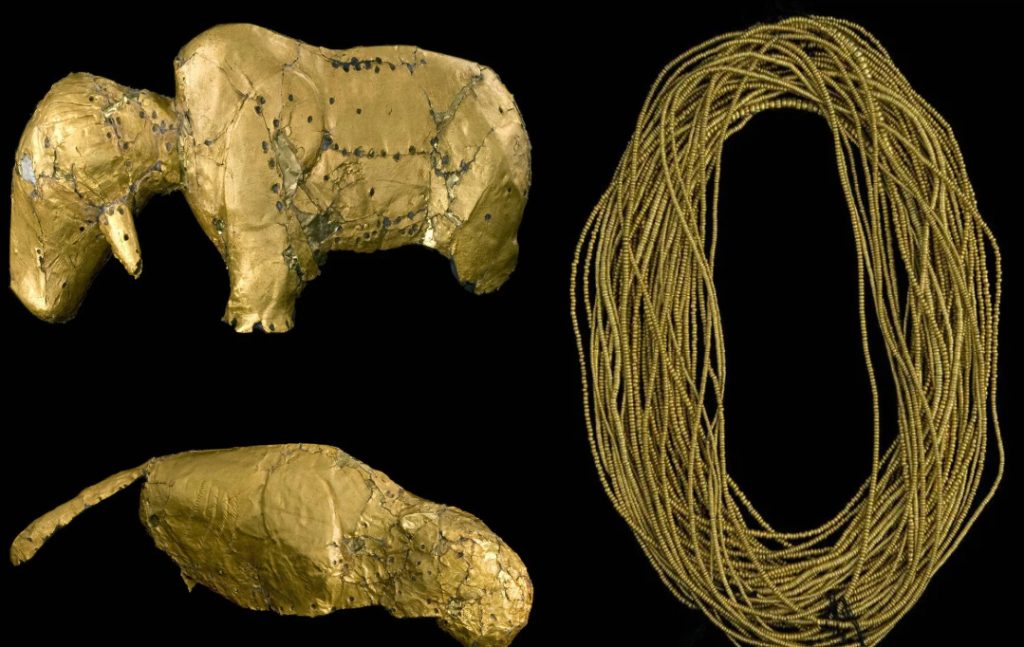

Most Notable Artefacts

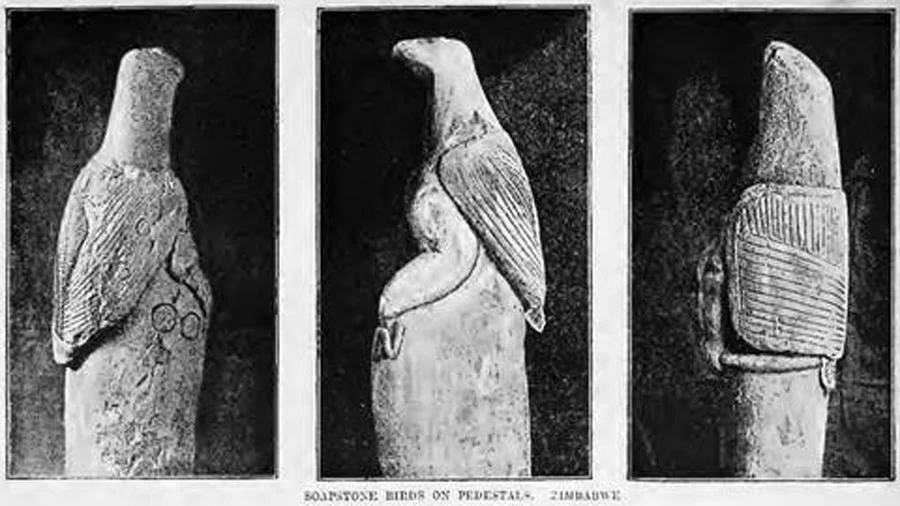

The most important artefacts recovered from the Monument are the eight Zimbabwe Birds. These were carved from a micaceous schist (soapstone) on the tops of monoliths the height of a person. Slots in a platform in the Eastern Enclosure of the Hill Complex appear designed to hold the monoliths with the Zimbabwe birds, but as they were not found in situ, the original location of each monolith and bird within the enclosure cannot be determined.

Other artefacts include soapstone figurines (one of which is in the British Museum), pottery, iron gongs, elaborately worked ivory, iron and copper wire, iron hoes, bronze spearheads, copper ingots and crucibles, and gold beads, bracelets, pendants and sheaths. Glass beads and porcelain from China and Persia among other foreign artefacts were also found, attesting the international trade linkages of the Kingdom. In the extensive stone ruins of the great city, which still remain today, include eight, monolithic birds carved in soapstone. It is thought that they represent the bateleur eagle – a good omen, protective spirit and messenger of the gods in Shona culture.

Centre For Trading

Archaeological evidence suggests that Great Zimbabwe became a centre for trading, with artefacts suggesting that the city formed part of a trade network linked to Kilwa and extending as far as China. Copper coins found at Kilwa Kisiwani appear to be of the same pure ore found on the Swahili coast. This international trade was mainly in gold and ivory. That international commerce was in addition to the local agricultural trade, in which cattle were especially important. The large cattle herd that supplied the city moved seasonally and was managed by the court. Chinese pottery shards, coins from Arabia, glass beads and other non-local items have been excavated at Zimbabwe. Despite these strong international trade links, there is no evidence to suggest exchange of architectural concepts between Great Zimbabwe and centres such as Kilwa.